Misinformation Watch: Book Bans in the United States

Book bans, especially with political intentions, are nothing new in the United States – or even just the states.

The first one on American soil pre-dates the uniting of the federation itself. In 1637, what is widely considered the first American book ban took place in Quincy, Massachusetts, when Thomas Morton’s New English Canaan was outlawed by a Puritan government that considered it “a harsh and heretical critique of Puritan customs and power structures,” according to Harvard.

Today, book bans and book challenges remain part of U.S. power struggles and culture war. Presently, most debates over limiting book access are rooted in America’s history of racial and ethnic relations, LGBTQ+ issues, and extremist causes.

Whether rooted in media bias or misinformation, think tanks and news sources from left to right sometimes miss the distinction between a “book ban” and a “book challenge.” Sometimes books are banned entirely, but other times, titles are “challenged” but not necessarily removed.

Here’s a breakdown of studies on which books have been banned, and how some sources have misled on the issue.

What Think Tanks Have Said on “Book Bans”

Coverage of specific books being banned often ties back to the work of the nonprofit PEN America. According to its website, PEN “works to ensure that people everywhere have the freedom to create literature, to convey information and ideas, to express their views, and to access the views, ideas, and literatures of others.”

This past September, PEN released an in-depth report analyzing book bans in schools from July 2021 to June 2022. It defines a “school book ban” as follows:

Any action taken against a book based on its content and as a result of parent or community challenges, administrative decisions, or in response to direct or threatened action by lawmakers or other governmental officials, that leads to a previously accessible book being either completely removed from availability to students, or where access to a book is restricted or diminished.

The report found 2,532 instances of bans which affected 1,648 unique book titles, and notes that “there are likely additional bans that have not been reported.” Those 1,648 titles were created by 1,553 unique authors, illustrators, or translators.

Some of the notable figures that drove media coverage came from PEN’s conclusions that books with LGBTQ themes and protagonists of color were among the highest percentage of topics banned.

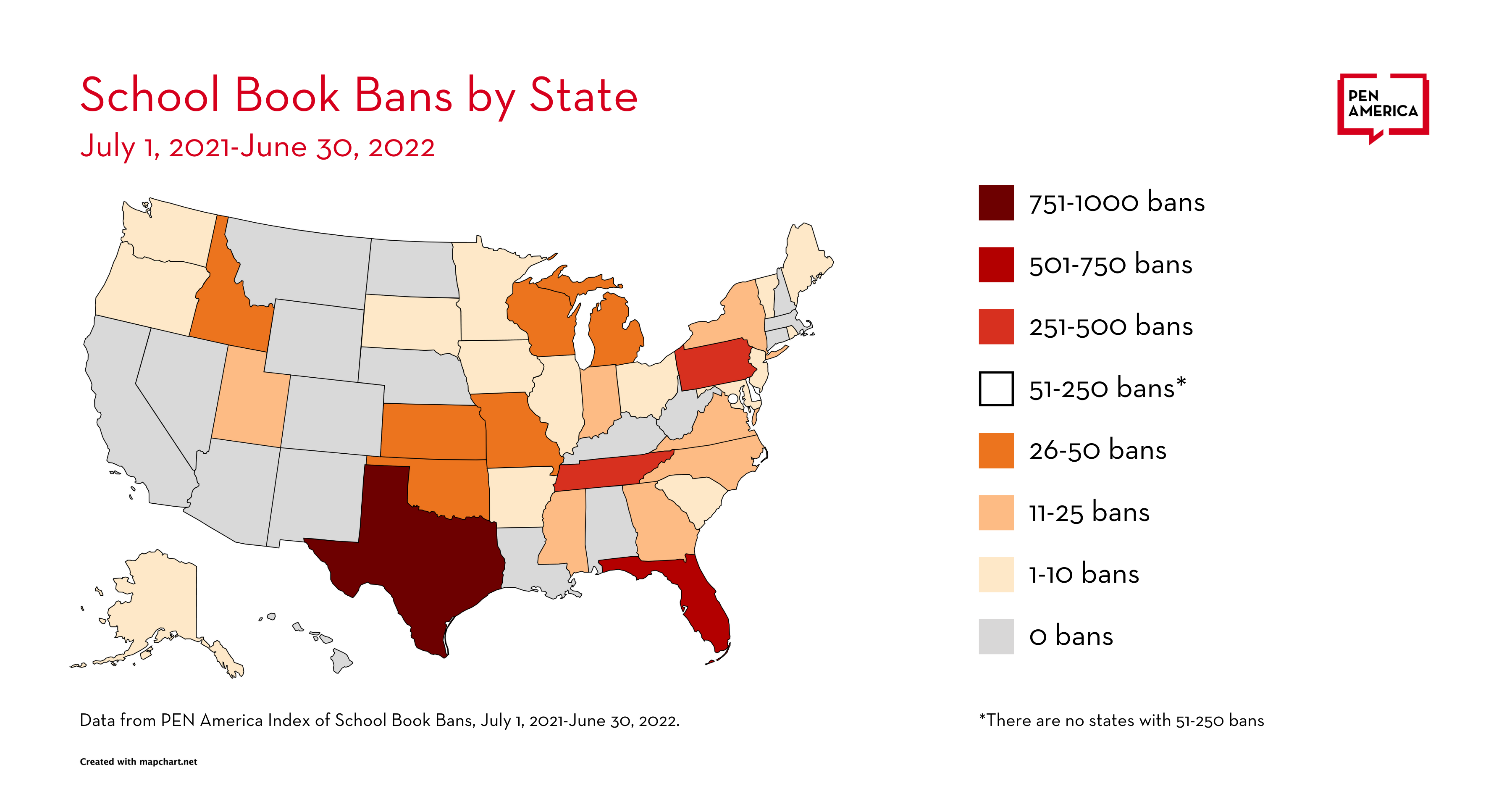

The states in which PEN found the most bans occurred were also of note. Texas had the most bans by far with 801. Three other states had a high number of bans: Florida with 566, Pennsylvania with 457, and Tennessee with 349. From there, the drop-off was stark. In fifth place was Oklahoma with 43 bans.

PEN estimated that at least 40% of the 2,532 instances were “connected to either proposed or enacted legislation, or to political pressure exerted by state officials or elected lawmakers to restrict the teaching or presence of certain books or concepts.”

Such legislation at the state level included the notable Parental Rights in Education Act (often dubbed the “Don’t Say Gay” law) signed by Florida Governor Ron DeSantis in March 2022. PEN said the law, combined with “outside monitoring of curricular and book choices in classrooms,” had accomplished “what was intended” in creating “a chilling effect on teaching and learning.”

RELATED: Misinformation Watch: Florida’s Parental Rights in Education Law

PEN identified 50 groups pushing for bans on a national level, some of which “espouse Christian nationalist political views.”

Florida and Texas were the most-mentioned states in the analysis: 22 times each. For context, Pennsylvania and Tennessee were mentioned four and six times, respectively, with most other states being mentioned less.

PEN framed its findings “against the backdrop of other efforts to roll back civil liberties and erode democratic norms,” as laid out by U.S. state-funded think tank Freedom House.

According to Influence Watch, Freedom House has received significant grants from entities like Google, Meta, and billionaire left-wing donor George Soros. It has been criticized in recent years by The Washington Post (Lean Left), The Heritage Foundation (Lean Right), and Tucker Carlson (Right) for being too heavily relied upon by U.S. policymakers and media outlets.

PEN calls its report “a canary in the coal mine for the future of American democracy, public education, and free expression,” and says, “We should heed this warning,” presumably referring to all Americans.

Another report that has been cited in some book ban reporting is the ALA’s 2023 report that tracked “book challenges” in 2022. The director of the ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom stated, “A book challenge is a demand to remove a book from a library’s collection so that no one else can read it.”

The ALA found 2,571 unique titles were targeted in 1,269 challenges. They report the number of unique titles affected is a 38% increase from 2021, and of the challenges, 58% targeted books in schools, while 41% targeted works in public libraries. ALA says, “The vast majority (of books targeted) were written by or about members of the LGBTQIA+ community and people of color.”

ALA also posted a second analysis, derivative of the original report on their website breaking down figures. It compiled findings into an interactive map where readers can view the number of challenges, titles challenged, and most challenged titles in each state. However, on this page, ALA offers statistics that conflict with their original report. On this page, ALA says 51% of challenges occurred in schools, and 48% occurred in public libraries. This could presumably be a typo, where the second digit of each figure was conflated with each other. AllSides has reached out to ALA for clarification.

For 2022, the states with the most challenges were Texas, Florida, Pennsylvania, and Michigan, similar to PEN’s report on bans, which shared 6 months of overlap with ALA’s report.

There’s one important difference in how PEN and ALA track efforts to suppress books. PEN tracks “book bans,” and defines any instance of access to a book being “diminished” as a “ban.” ALA doesn’t mention the word “ban” in its report and instead focuses on the challenges themselves (whether the challenges are successful or not).

This key distinction, however, is sometimes lost in biased media coverage.

What News Sources and Analysts Have Said on “Book Bans”

Naturally, reporting on such widespread “bans” happening in Republican strongholds Florida and Texas sparked coverage from sources across the political spectrum. PEN and ALA themselves are both described as “left-of-center” by Influence Watch, and media coverage — which was more polarizing in regards to PEN’s report — reflected that.

Media coverage from left to right differed in framing the “bans.” Many left-rated sources framed calls to restrict some books in schools as undue censorship, and attacks on the LGBTQ+ community and racial minorities. Some right-rated sources, meanwhile, framed the “bans” as necessary suppression of left-wing attempts to sexualize children or advance undue guilt for America’s history of slavery.

Well before either the ALA or PEN reports were published, CBS News (Lean Left) had already conducted some polling on book bans, which PEN cited in its report. The surveys found that Americans, regardless of political affiliation, overwhelmingly reject in-school book bans on the premise of discussing race. LGBTQ matters were not included in the polling.

Major left-leaning news outlets like NBC News (Lean Left) or NPR (Lean Left) promptly featured PEN’s report, highlighting the findings that books involving race or LGBTQ themes were among the most banned in PEN’s investigation.

Coverage of PEN’s findings from the right was significantly thinner, and when it did appear, it was often oppositional to PEN’s findings. For instance, Fox News (Right) posted an article a week after the report made headlines, debunking one of PEN’s claims as incorrectly labeling a book as banned, that in fact remained on the school in question’s shelves.

The Heritage Foundation criticized PEN’s “expansive view of book banning” shortly after the report was published. On May 11, The Daily Signal (Right), which is owned by Heritage, published a report summarizing a recent investigation it conducted in response to PEN’s report. The report disputed the claim that there were 2,532 instances of titles being removed from schools.

Heritage found that 74% of the books PEN “identified as banned” were still active in school libraries, with some being checked out at the time of the investigation. Heritage was unable to confirm whether the other 26% of books had been previously available and were now banned, or whether they ever existed in school catalogs.

The report also disputed PEN’s report that many classic works like Anne Frank’s Diary, Brave New World, Lord of the Flies, Of Mice and Men, The Color Purple, and To Kill a Mockingbird were banned, reporting, “In every school district in which PEN America alleges those books were banned, we found copies listed as available in the online card catalog.”

Heritage said of the books it was unable to find in school libraries, most were of LGBTQ or sexual themes, including Gender Queer, Flamer, Lawn Boy, Fun Home, and It’s Perfectly Normal: Changing Bodies, Growing Up, Sex, and Sexual Health.

The Washington Post also conducted a “first-of-its-kind” analysis of book challenges that was derivative of PEN’s investigation. The Post found that 43% of claims tracked by PEN “targeted titles with LGBTQ characters or themes, while 36 percent targeted titles featuring characters of color or dealing with issues of race and racism.”

Out of 986 total challenges in school libraries, 61% of complaints listed “sexual” content as a reason, and 18% of complaints listed “LGBTQ.” Between them were flags such as “alcohol/drug use,” “pornographic,” and “graphic.” Eight percent of complaints cited “racist” as a reason for the challenge.

Some local sources have also relied on PEN’s list of targeted books. MLive.com, a Michigan-focused source, published an article titled, See which books are banned in Michigan schools. The article begins with an Editor’s Note clarifying that PEN’s list “was tracked from January to June of 2022” and “some of these books may be back on shelves pending investigations.”

ALA’s report was sent to the press in a release dated March 22, and most media outlets featured it on April 24. (Being as though April 22 was a Saturday and April 24 was the first business day following it, AllSides believes this March date may be another typo and has reached out for clarification.) The report was covered mostly by left-rated outlets like PBS NewsHour (Lean Left), and NPR, but also received news coverage from Washington Times (Lean Right), and The Hill (Center).

The Daily Signal criticized the ALA for “blaming anti-LGBT prejudice for what it calls censorship even though each book contains sexually explicit content.” In the article, The Daily Signal linked back to an opinion it published on March 31, arguing that there aren’t any truly banned books in the United States.

Book bans have been a consistent topic for fact-checkers across the spectrum, including AP Fact Check (Lean Left) and Snopes (Lean Left), which have highlighted fake lists of “banned books” that have circulated online.

Most recently, in Joe Biden’s 2024 campaign announcement video, the President described efforts by “MAGA extremists” to ban books as To Kill a Mockingbird appeared on the screen. This sparked a fact check from Free Beacon Fact Check (Right), which framed the implication as “misinformation” spread by “liberals,” citing AP Fact Check’s aforementioned analysis confirming the title is not banned in Florida.

U.S. Legislation and Political Action Regarding Books

According to Book Riot, the self-described largest independent literary site in North America, states like Florida, Texas, Tennessee, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Utah have “some of the biggest” laws in place that indirectly ban some books on certain subject matters from schools. Most of these laws aim to restrict “obscene,” or “sexual” subject matters from schools.

A law in Oklahoma bans critical race theory from classrooms, something Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin has enacted in his state as well. As PEN’s report stated, Florida’s Parental Rights in Education Act is a probable cause for spikes in book challenges in the state.

At a federal level, there is not currently any legislation in place that bans books from schools. Beyond that, according to Wikipedia, federal, state, or local U.S. governments have banned 20 books throughout the nation’s history. Of the 20 listed, AllSides has determined that three still face some sort of restriction.

The Federal Mafia, penned by Irwin Schiff in 1992, is barred from store shelves because of a 2004 ruling by the federal appeals court, so Schiff offered it for free online. An unauthorized sequel to The Catcher in the Rye, which was not written by the original author J.D. Salinger, titled 60 Years Later: Coming through the Rye, remains banned from sale in the United States on the grounds of a legal suit from Salinger. Operation Dark Heart, a memoir by a retired U.S. intelligence officer who served in Afghanistan, faced government obstruction upon its publication and is now published with redactions, as several Federal Intelligence Agencies claimed the text discussed classified matters.

Conclusion

The widespread media coverage of book challenges and bans has stemmed mostly from a few key reports on book challenges. Individuals or groups brought most of these challenges. However, it appears sweeping law changes by government officials have indirectly opened the door for more challenges of certain groups of books and led to a few reactionary book withdrawals from schools.

When reading about book bans and challenges, it’s important to understand the difference between the two, and to seek coverage from media outlets of different biases to avoid putting too much stock in overtly biased or misinformed conclusions.

Andy Gorel is a News Curator at AllSides. He has a Center bias.

This piece was reviewed by Joseph Ratliff, Daily News Editor (Lean Left bias), Julie Mastrine, Director of Marketing and Media Bias Ratings (Lean Right bias), and Henry A. Brechter, Editor-in-Chief (Center bias).

April 19th, 2024

April 19th, 2024

April 18th, 2024

April 17th, 2024